Algorithms

Hey there! Thanks for your patience as I build out this page and make it a vastly more interactive experience with integrated Jupyter Notebooks.

Below are some blocks of code that demonstrate some basic capabilities of mine. Consider these fun side-projects; unfortunately I am not allowed to share any of my previous work experience, as most of it contains highly sensitive information and trade secrets. But I can still demonstrate basic functionality in hypothetical environments!

With that being said, let’s dive into some of the best financial algorithm practices!

Table of Contents

- Interest Rate Modeling with the Hull-White Model

- SAS Regression for House Price Prediction

- Implementing a Simple Trading Strategy using C++

- Automated Trading with Interactive Brokers (IBKR) through Python

- Distributed Systems and Blockchain

- Stock Price Simulation Using Geometric Brownian Motion (GBM)

- Default Probability Simulation Using Monte Carlo Methods

Interest Rate Modeling with the Hull-White Model

Interest rate models are crucial for pricing derivatives and managing interest rate risk to banking and credit portfolios. One of the most popular models used by quants and financial engineers is the Hull-White Model, with its mean-reverting property as a particuarly useful method for modeling interest rates over time. It captures the tendency of interest rates to revert to a long-term mean, making it suitable for valuing interest rate derivatives and managing interest rate risk.

Here is the wiki page on the Hull-White Model if you would like to learn more about the fundamentals of this method:

Wikipedia - Hull-White model

In this section, I’ll walk you through a basic implementation of the Hull-White model in C++ with the assumption that we are fetching live interest rate data from a cloud data source. This approach will be practical and relevant for real-world applications in a portfolio trading environment.

#include <iostream>

#include <cmath>

#include <vector>

#include <random>

#include <curl/curl.h>

#include <json/json.h>

// Hull-White model parameters

const double a = 0.1; // mean reversion rate

const double sigma = 0.01; // volatility

// function to fetch live interest rate data from cloud

std::vector<double> fetchInterestRateData(const std::string& url) {

CURL* curl;

CURLcode res;

std::string readBuffer;

curl = curl_easy_init();

if(curl) {

curl_easy_setopt(curl, CURLOPT_URL, url.c_str());

curl_easy_setopt(curl, CURLOPT_WRITEFUNCTION, WriteCallback);

curl_easy_setopt(curl, CURLOPT_WRITEDATA, &readBuffer);

res = curl_easy_perform(curl);

curl_easy_cleanup(curl);

}

Json::Value jsonData;

Json::Reader jsonReader;

if (jsonReader.parse(readBuffer, jsonData)) {

std::vector<double> rates;

for (const auto& rate : jsonData["rates"]) {

rates.push_back(rate.asDouble());

}

return rates;

} else {

throw std::runtime_error("Failed to parse JSON data");

}

}

// callback function for curl to write data

size_t WriteCallback(void* contents, size_t size, size_t nmemb, void* userp) {

((std::string*)userp)->append((char*)contents, size * nmemb);

return size * nmemb;

}

// function to generate random number from standard normal distribution

double generateGaussianNoise() {

static std::default_random_engine generator;

static std::normal_distribution<double> distribution(0.0, 1.0);

return distribution(generator);

}

// function to simulate interest rate path using Hull-White model

std::vector<double> simulateInterestRatePath(const std::vector<double>& initialRates, double dt, int steps) {

std::vector<double> r(steps); // vector to store interest rates

r[0] = initialRates.back(); // initial interest rate

for (int i = 1; i < steps; ++i) {

// generate random number from standard normal distribution

double dW = sqrt(dt) * generateGaussianNoise();

// apply Hull-White model equation

r[i] = r[i-1] * exp(-a * dt) + (1 - exp(-a * dt)) * sigma * dW;

}

return r; // return the simulated interest rate path

}

int main() {

// URL to fetch live interest rate data

std::string url = "https://api.example.com/interest-rates";

try {

// fetch initial interest rate data

std::vector<double> initialRates = fetchInterestRateData(url);

double timeStep = 0.01; // time step size

int numSteps = 100; // number of steps in simulation

// simulate interest rate path

std::vector<double> rates = simulateInterestRatePath(initialRates, timeStep, numSteps);

// print the simulated interest rates

for (double rate : rates) {

std::cout << rate << std::endl;

}

} catch (const std::exception& ex) {

std::cerr << "Error: " << ex.what() << std::endl;

return 1;

}

return 0;

}

Explanation

Fetching Live Interest Rate Data

To make the simulation more realistic, we fetch live interest rate data from a cloud data source using the libcurl library and parse the JSON response using the jsoncpp library.

- fetchInterestRateData:

This function takes a URL as an argument, fetches the interest rate data from the specified API, and returns a vector of interest rates. - WriteCallback:

This is a callback function used by curl to write the data fetched from the API into a string. Generating Gaussian Noise - To simulate the randomness in interest rate movements, we use the generateGaussianNoise function, which generates random numbers from a standard normal distribution using C++’s

library.

Simulating Interest Rate Paths

The simulateInterestRatePath function simulates interest rate paths using the Hull-White model explained above. It takes the initial interest rates, the time step size (dt), and the number of steps (steps) as input. The function iterates over the number of steps, applying the Hull-White model equation to generate the path of interest rates.

Main Function

In the main function, we:

- Define the URL to fetch live interest rate data.

- Fetch the initial interest rate data.

- Define the time step size and the number of simulation steps.

- Simulate the interest rate path using the Hull-White model.

- Print the simulated interest rates.

We’ve implemented the Hull-White interest rate model in C++. By fetching live interest rate data from a theoretical cloud data source and simulating future interest rate paths, we can better manage portfolio interest rate risk and price derivatives easily. This basic approach demonstrates the practical application of quantitative rate modeling with C++!

SAS Regression for House Price Prediction

In this section, we are exploring my favorite technology for standard regression (perhaps an unpopular opinion), which is SAS. This SAS program detailed below demonstrates fitting and analyzing a multiple regression model using the procedures REG, GLM (General Linear Model) and PLM (Post Linear Model).

We’ll use PROC REG to run a linear regression model with two predictors and then use PROC GLM to fit the same model to show additional plots. We’ll save the analysis results in an item store and use PROC PLM for further analysis.

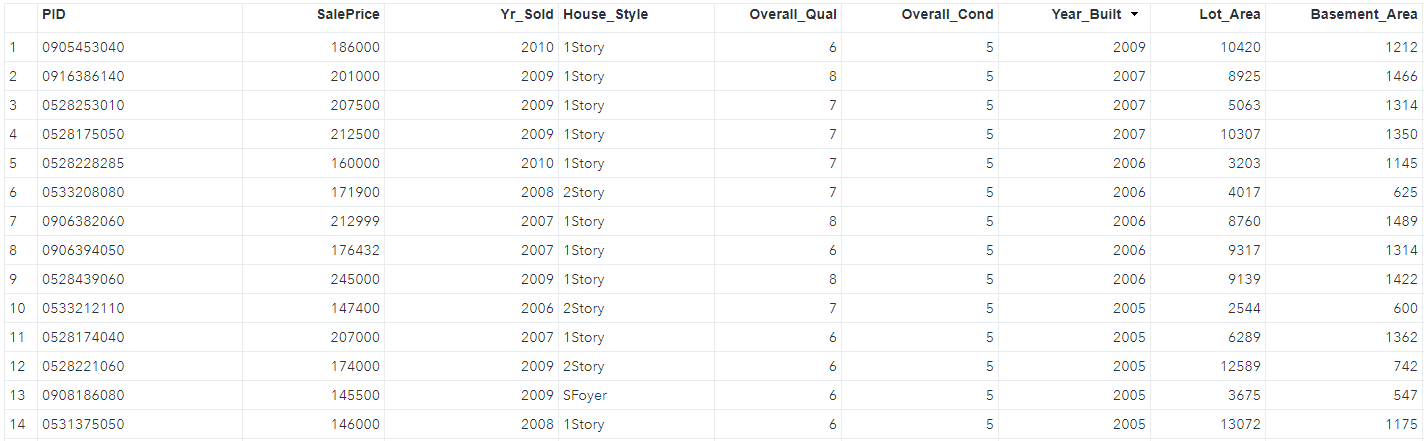

Let’s assume we have a table of data in SAS, called HousingData in the FOLDER folder (I know, I’m extensively creative). See the screenshot below for what some of our data may look like. A real database such as YardiMatrix or CoStar would have many fields/columns here that we would be able to choose from in our model, but we will keep things simple for this demonstration and only use the SalePrice, Basement_Area, and Lot_area fields.

Part A: Fitting the Model with PROC REG

In the below code, we specify SalePrice as the response variable, and Basement_Area and Lot_Area as predictors. In the output, the Analysis of Variance table shows that the model is statistically significant with an R-square of 0.4802, indicating that 48% of the variability in SalePrice is explained by Basement_Area and Lot_Area.

proc reg data=FOLDER.HousingData ;

model SalePrice=Basement_Area Lot_Area;

title "Model with Basement Area and Lot Area";

run;

Here are is the resulting output of the above code (yes, this entire output is the result of the above 4 lines of code!):

The Analysis of Variance table shows that this model is statistically significant at the 0.05 alpha level, with a p-value of less than the alpha at <.0001. However, if you look at Lot_Area specifically, it does not have statistical significance, as its p-value of 0.1032 is more than our alpha of 0.05, showcasing that the lot size is not a significant predictor of the house’s sale price when we are already controlling for the basement.

That is an interesting detail! In plain english, this means that Lot_Area and Basement_Area are correlated, and Lot_Area does not explain significant variation in SalePrice over and above Basement_Area. If these were our only predictors, we’d consider removing Lot_Area from the model, but we might decide to add other predictors instead. The additional predictors might change the p-values for Lot_Area and Basement_Area, so it’s best to wait to see the full model before discarding non-significant terms.

The residuals plotted against predicted values give us a relatively random scatter around 0. They provide evidence that we have constant variance. In the Q-Q plot, the residuals fall along the diagonal line, and they look approximately normal in the histogram. This indicates that there are no problems with an assumption of normally distributed error.

Next, we see the residuals plotted against the predictor variables. Patterns in these plots are indications of an inadequate model. The residuals show no pattern, although lot size does show a few outliers.

Part B: Further analysis with PROC GLM

In this step, we’ll run the same model in PROC GLM, requesting a contour plot and an item store named multiple to be further analyzed later.

proc glm data=FOLDER.HousingData plots(only)=(contourfit);

model SalePrice = Basement_Area Lot_Area;

store out=multiple;

title "Model with Basement Area and Lot Area";

run;

quit;

- PROC GLM fits a general linear regression model to our data, predicting SalePrice using the Basement_Area and Lot_Size fields.

- The predictor/target outcome SalePrice is our dependent/response variable, while Basement_Area and Lot_Area are our independent or predictive variables.

store out=multiple;saves the model results in an item store named ‘multiple’ that will be called in our next SAS snippet as a new table for further analysis and visualization.

Below is the output result of the above code. The reason I love SAS so much is because it is designed to do the majority of the work for you. If you were framing this up in Python or another language, you would need a bunch of code to also handle the printing of the outputs.

PROC GLM Output:

In the results, we see that the values in the ANOVA table are the same as in PROC REG. The parameter estimates table gives the same results (within rounding error) as in PROC REG. We can use this contour fit plot with the overlaid scatter plot to see how well the model predicts observed values.

The plot shows predicted values of SalePrice as gradations of the background color from blue, representing low values, to red, representing high values. The dots are similarly colored, and represent the actual data. Observations that are perfectly fit would show the same color within the circle as outside the circle. The lines on the graph help you read the actual predictions at even intervals. For example, this point near the upper right represents an observation with a basement area of approximately 1,500 square feet, a lot size of approximately 17,000 square feet, and a predicted value of more than $180,000 for sale price. However, the dot’s color shows that its observed sale price is actually closer to $160,000.

Part C: Visualizing the Model with PROC PLM

Now, we’ll use PROC PLM to process the item store created by PROC GLM and create additional plots. The EFFECTPLOT statement produces a display of the fitted model and provides options for changing and enhancing the displays. The EFFECTPLOT option, CONTOUR, requests a contour plot of predicted values against two continuous predictors. We want Basement_Area plotted on the Y axis, and Lot_Area on the X axis. The SLICEFIT option displays a curve of predicted values versus a continuous variable grouped by the levels of another effect. We want to see the Lot_Area effect at different values of Basement_Area. with tick marks ranging from 250 to 1000, in increments of 250.

proc plm restore=multiple plots=all;

effectplot contour (y=Basement_Area x=Lot_Area);

effectplot slicefit(x=Lot_Area sliceby=Basement_Area=250 to 1000 by 250);

run;

title;

Notice that the lines in the contour fit plot are oriented differently than the plot from PROC GLM. The item store doesn’t contain the original data, so PROC PLM can show only the predicted values, not the individual observed values. Clearly, the PROC GLM contour fit plot from Part B is more useful, but if you don’t have access to the original data, and you can run PROC PLM on the item store, which gives you an idea of the relationship between the predictor variables and predicted values.

The last plot, a slice plot, is another way to display the results of a two-predictor regression model. This plot displays SalePrice by Lot_Area, categorized by Basement_Area. The regression lines represent the slices of Basement_Area that we specified in the code. As you can see, you have several options for visualizing and communicating the results of your analyses in SAS!

We’ve created a multiple regression model with two predictors, so what’s next?

From here, we would move on to test the remainder of our predictors in a larger multiple regression model. Data tables that have been pre-cleaned for machine learning formatting (no nulls, consistent data types) can provide each column as a predictor variable. There are many possible models that we could explore, but for now, I will move away from SAS and switch it up by going into automated trading algorithms!

Implementing a Simple Trading Strategy using C++

If you have ever been curious on how much code is required for automating a trading strategy, then you have come to the right place! It is actually quite easy to implement a basic solution on your own, even as a retail trader without access to the expensive mega-live-data packages that instituional clients get.

But of course, it is a vastly scalable technology, and to achieve a real competitive edge that can generate significant alpha, you will need to fine-tune these concepts across a wide range of technical considerations. Then of course, you would need to bring them all together to form what is what I like to call a trading organism; a highly-systematic workspace that contains functional objects and classes that talk to each other to form a comprehensive trading system.

But to get to the point where you have a multitude of scripts working for you - your little trading robot army - we need to understand the basic components of our frontline soldier.

Let’s start with a simple trading strategy using C++. This example demonstrates a moving average crossover strategy, which generates buy/sell signals based on short-term and long-term moving averages of stock prices. Moving averages help smooth out price data and identify trends over a specific period.

#include <iostream>

#include <vector>

// Function to calculate the moving average for a given period

double calculateMovingAverage(const std::vector<double>& prices, int period) {

if (prices.size() < period) return 0.0; // Not enough data points

double sum = 0.0;

for (int i = prices.size() - period; i < prices.size(); ++i) {

sum += prices[i];

}

return sum / period;

}

int main() {

// Sample stock prices (example data)

std::vector<double> prices = {234.56, 230.12, 240.00, 245.67, 250.89, 255.45, 260.00};

int shortPeriod = 9; // 9 day moving average

int longPeriod = 21; // 21 day moving average

// Loop through the prices to generate buy/sell signals based on moving averages

for (int i = longPeriod; i <= prices.size(); ++i) {

// Calculate short-term and long-term moving averages

double shortMA = calculateMovingAverage(std::vector<double>(prices.begin(), prices.begin() + i), shortPeriod);

double longMA = calculateMovingAverage(std::vector<double>(prices.begin(), prices.begin() + i), longPeriod);

// Generate trading signals based on moving average comparison

if (shortMA > longMA) {

std::cout << "Buy signal at price: $" << prices[i - 1] << std::endl;

} else if (shortMA < longMA) {

std::cout << "Sell signal at price: $" << prices[i - 1] << std::endl;

} else {

std::cout << "Hold at price: $" << prices[i - 1] << std::endl;

}

}

return 0;

}

Explanation

In this generalized script, we are utilizing the iostream and vector libraries for access to the standard operations such as std::cin and std:cout, as well as the container class std::vector. This is mostly just for providing the standard format, where we are defining a function that makes a specific calculation, and making the trade within the main class loop. We are taking a lot of assumptions here, but it’s important to digest what the basic trading code looks like.

Moving Average Calculation:

First, the calculateMovingAverage function is declared. This takes two parameters: a cpmstamt referemce tp a vextor of doubles (prices) and an integer (period). The function then computes and returns the average prices of the underlying over a specified period, or the moving average.

The if line checks if the size of the prices vector is less than the specified period. If true, it returns 0.0 because there are not enough data points to calculate the moving average. Then, after declaring the sum double variable, we use the for loop to start from prices.size() - period and runs until prices.size() - 1. It iterates through the last period number of elements in the prices vector. Within the loop, the += operator is used to add the prices[i] current price to the sum.

After the loop completes, the function returns the average by dividing sum by the period.

Initializing MAs:

Once the moving average for the particular period is calculated, the main function initializes stock prices through a vector declaration (this would be loaded from real-time data in a real application, perhaps daily closing candle prices) and defines our MA periods as the 9- and 21-day MAs. The main function then iterates through the prices with another for loop and utilizes the calculateMovingAverage function we defined to calculate the MAs, generating buy/sell signals based on their comparison.

double shortMA = calculateMovingAverage(std::vector<double>(prices.begin(), prices.begin() + i), shortPeriod);

double longMA = calculateMovingAverage(std::vector<double>(prices.begin(), prices.begin() + i), longPeriod);

The usage of these lines calculates the short- and long-term MA by calling the calculateMovingAverage function with a subvector of prices from the beginning to the i-th element and the Period length. Typically though, moving averages are only very reliable on the longer dated time frames; the further out the chart, the higher impact a cross of the MAs would indicate.

Trading Logic:

See the green and orange lines in the NVDA daily TradingView chart above. You should be able to play with this chart for viewing different time frames, as the MAs on this particular chart are locked in by the selected timeframe.

The if-statement within the for-loop is simulating the crossover of these MA lines on the chart.

// Generate trading signals based on moving average comparison

if (shortMA > longMA) {

std::cout << "Buy signal at price: $" << prices[i - 1] << std::endl;

} else if (shortMA < longMA) {

std::cout << "Sell signal at price: $" << prices[i - 1] << std::endl;

} else {

std::cout << "Hold at price: $" << prices[i - 1] << std::endl;

}

if (shortMA > longMA): This condition checks if the short-term moving average is greater than the long-term moving average.

std::cout << "Buy signal at price: $" << prices[i - 1] << std::endl;: If the condition is true, it prints a “Buy signal” with the current price.

else if (shortMA < longMA): This condition checks if the short-term moving average is less than the long-term moving average.

std::cout << "Sell signal at price: $" << prices[i - 1] << std::endl;: If the condition is true, it prints a “Sell signal” with the current price.

else: This condition is met if the short-term and long-term moving averages are equal, which should practically be almost never, but we still need to factor it in as a possible outcome to prevent the script from breaking.

std::cout << "Hold at price: $" << prices[i - 1] << std::endl;: If the condition is true, it prints a “Hold” signal with the current price.

This is a basic strategy that relies on the moving averages for generating buy/sell signals in C++. Only relying on MAs, especially on the longer-dated time frames, means you will miss out on the first-half or so of most directional runs, and is far from a reliable strategy. Implementing this code with a combination of previous resistance/support levels could be a better solution to try out.

Automated Trading with Interactive Brokers (IBKR) through Python

For retail traders like myself, Interactive Brokers (IBKR) offers an awesome and powerful platform for automated trading within Python, enabling us to almost compete with institutional investors to execute advanced trading strategies using real-time data and historical pricing (okay I’m joking). But regardless, implementing automated options trading through IBKR can be a fantastic method of generating alpha through mean-reversion methods, which I will detail below. Warning: this section is a bit more dense, but I have provided comments on every functional line of code for added context.

I usually implement my personal projects using the ib_insync library in Python, which provides an intuitive way to work with the IBKR API, allowing you to directly connect your python scripts to your brokerage - real accounts and paper alike! This approach allows for the development of strategies ranging from simple moving average crossovers like the above C++ strategy to more complex strategies involving machine learning predictions. Sometimes I also use the tradingview_ta package to leverage TradingView’s powerful and highly customizable technical analysis indicators generated in Pine script. By integrating these tools, I can automate my trading strategies effectively, making real-time decisions based on market conditions.

In this example, we will explore an automated trading strategy that combines the power of Python, TradingView, and QuantLib to trade options spreads on the S&P 500 Index (SPX). The strategy utilizes VWAP (Volume Weighted Average Price) levels to generate buy and sell signals. We will fetch live price data from TradingView, use these signals to determine market conditions, and calculate theoretical option prices with QuantLib.

To implement the VWAP indicators, we will integrate custom Pine scripts within TradingView. These scripts will generate the necessary buy and sell signals based on VWAP levels, which our Python script will then fetch and use to execute trades. By setting up these indicators in TradingView and connecting to IBKR, we can automate the execution of bull call spreads and bear put spreads based on real-time market data.

This tutorial will guide you through the entire process: connecting to Interactive Brokers, fetching live market data, integrating Pine script indicators in TradingView, calculating options prices, and executing trades automatically. Whether you’re a retail trader looking to enhance your trading capabilities or an aspiring quant eager to dive into algorithmic trading, this example provides a robust framework for developing and implementing sophisticated trading strategies.

Automated Bull Call and Bear Put Spreads on SPX with Interactive Brokers (IBKR)

Automated trading strategies using Interactive Brokers (IBKR) can be highly effective for options trading, particularly for spread strategies where your risk is defined.

In this example, I am showcasing bull call spreads and bear put spreads, which are useful for directional strategies.

Example: Bull Call and Bear Put Spreads Trading Strategy

from ib_insync import *

import time

from tradingview_ta import TA_Handler, Interval, Exchange

import QuantLib as ql

# Function to fetch VWAP signal from TradingView

def get_vwap_signals():

handler = TA_Handler(

symbol="SPX", # Symbol for SPX

screener="america", # Screener region

exchange="SPX", # Exchange name

interval=Interval.INTERVAL_1_DAY # Data interval (daily)

)

analysis = handler.get_analysis() # Fetch analysis from TradingView

buy_signal = analysis.summary['RECOMMENDATION'] == 'BUY' # Check for buy signal

sell_signal = analysis.summary['RECOMMENDATION'] == 'SELL' # Check for sell signal

return buy_signal, sell_signal # Return signals

# Function to fetch the current price of SPX from TradingView

def get_current_price():

handler = TA_Handler(

symbol="SPX", # Symbol for SPX

screener="america", # Screener region

exchange="SPX", # Exchange name

interval=Interval.INTERVAL_1_DAY # Data interval (daily)

)

analysis = handler.get_analysis() # Fetch analysis from TradingView

current_price = analysis.indicators['close'] # Extract the closing price

return current_price # Return the current price

# Function to determine the strike prices for the spreads

def get_strike_prices(current_price, step=50):

# Assuming option strikes are in increments of 50

next_otm_strike = ((current_price // step) + 1) * step # Calculate the next OTM strike

third_otm_strike = ((current_price // step) + 3) * step # Calculate the third OTM strike

return next_otm_strike, third_otm_strike # Return the calculated strike prices

# Function to determine exit signal based on VWAP bands

def check_exit_signals(price, upper_band, lower_band):

if price >= upper_band or price <= lower_band: # Check if price hits VWAP bands

return 'exit' # Return exit signal

return 'hold' # Return hold signal

# Function to calculate the theoretical option price using QuantLib

def calculate_option_price(spot_price, strike_price, maturity_date, option_type='call'):

# Market data

risk_free_rate = 0.01 # Risk-free rate

dividend_yield = 0.0 # Dividend yield

volatility = 0.20 # Volatility

# QuantLib setup

calculation_date = ql.Date.todaysDate()

ql.Settings.instance().evaluationDate = calculation_date

maturity = ql.Date(maturity_date.day, maturity_date.month, maturity_date.year)

# Option details

payoff = ql.PlainVanillaPayoff(ql.Option.Call if option_type == 'call' else ql.Option.Put, strike_price)

exercise = ql.EuropeanExercise(maturity)

# Construct the option

european_option = ql.VanillaOption(payoff, exercise)

# Construct the market environment

spot_handle = ql.QuoteHandle(ql.SimpleQuote(spot_price))

flat_ts = ql.YieldTermStructureHandle(ql.FlatForward(calculation_date, risk_free_rate, ql.Actual360()))

dividend_yield = ql.YieldTermStructureHandle(ql.FlatForward(calculation_date, dividend_yield, ql.Actual360()))

vol_handle = ql.BlackVolTermStructureHandle(ql.BlackConstantVol(calculation_date, ql.NullCalendar(), volatility, ql.Actual360()))

# Black-Scholes-Merton Process

bsm_process = ql.BlackScholesMertonProcess(spot_handle, dividend_yield, flat_ts, vol_handle)

# Pricing the option

european_option.setPricingEngine(ql.AnalyticEuropeanEngine(bsm_process))

price = european_option.NPV()

return price

# Main trading logic

def trade_spx_spreads():

ib = IB() # Initialize IBKR connection

ib.connect('127.0.0.1', 7497, clientId=1) # Connect to IBKR TWS or Gateway

while True:

# Fetch VWAP signals

buy_signal, sell_signal = get_vwap_signals()

# Fetch the current SPX price

current_price = get_current_price()

# Determine the strike prices for the spreads

next_otm_strike, third_otm_strike = get_strike_prices(current_price)

# Define the expiration date

expiration_date = ql.Date(21, 6, 2024) # 21st June 2024

# Calculate theoretical option prices using QuantLib

call_price1 = calculate_option_price(current_price, next_otm_strike, expiration_date, option_type='call')

call_price2 = calculate_option_price(current_price, third_otm_strike, expiration_date, option_type='call')

put_price1 = calculate_option_price(current_price, next_otm_strike, expiration_date, option_type='put')

put_price2 = calculate_option_price(current_price, third_otm_strike, expiration_date, option_type='put')

# Print theoretical prices for debugging

print(f"Call Option {next_otm_strike}: {call_price1}")

print(f"Call Option {third_otm_strike}: {call_price2}")

print(f"Put Option {next_otm_strike}: {put_price1}")

print(f"Put Option {third_otm_strike}: {put_price2}")

# Define the SPX option contracts for spreads at specific strike and date

spx_call1 = Option('SPX', '20240621', next_otm_strike, 'C', 'SMART') # Next OTM call option

spx_call2 = Option('SPX', '20240621', third_otm_strike, 'C', 'SMART') # Third OTM call option

spx_put1 = Option('SPX', '20240621', next_otm_strike, 'P', 'SMART') # Next OTM put option

spx_put2 = Option('SPX', '20240621', third_otm_strike, 'P', 'SMART') # Third OTM put option

# Request market data for the options

ib.reqMktData(spx_call1)

ib.reqMktData(spx_call2)

ib.reqMktData(spx_put1)

ib.reqMktData(spx_put2)

ib.sleep(2) # Sleep to allow time for data retrieval

# Execute trades based on VWAP signals

if buy_signal:

print("Entering bull call spread, market bullish")

buy_call = MarketOrder('BUY', 1)

sell_call = MarketOrder('SELL', 1)

ib.placeOrder(spx_call1, buy_call) # Buy next OTM call

ib.placeOrder(spx_call2, sell_call) # Sell third OTM call

elif sell_signal:

print("Entering bear put spread, market bearish")

buy_put = MarketOrder('BUY', 1)

sell_put = MarketOrder('SELL', 1)

ib.placeOrder(spx_put1, buy_put) # Buy next OTM put

ib.placeOrder(spx_put2, sell_put) # Sell third OTM put

else:

print("No trade signal")

time.sleep(60) # Wait for a minute before checking signals again

# Simulate market data updates (in real scenario, this would be a continuous process)

print(f"Current price: {current_price}")

# Check for exit signals

vwap, upper_band, lower_band = get_vwap_bands()

exit_signal = check_exit_signals(current_price, upper_band, lower_band)

if exit_signal == 'exit':

print("Exiting position, price hit VWAP band")

if buy_signal:

close_call1 = MarketOrder('SELL', 1)

close_call2 = MarketOrder('BUY', 1)

ib.placeOrder(spx_call1, close_call1)

ib.placeOrder(spx_call2, close_call2)

elif sell_signal:

close_put1 = MarketOrder('SELL', 1)

close_put2 = MarketOrder('BUY', 1)

ib.placeOrder(spx_put1, close_put1)

ib.placeOrder(spx_put2, close_put2)

break # Exit loop after closing position

# Disconnect from IB after trades

ib.disconnect()

# Assuming this script runs within a trading environment setup

trade_spx_spreads()

Explanation

Fetching VWAP Data:

The get_vwap_bands function simulates fetching Volume Weighted Average Price (VWAP) data along with upper and lower bands. In my implementation within the custom Pine script, we are using the 0.5, 1, and 2 standard deviations for our potential buy/sell signals depending on the price direction.

VWAP Signals:

The check_vwap_signals function determines the trading signal (bull call spread, bear put spread, neutral) based on the current price relative to the VWAP bands. As implemented here, we are only getting the first standard deviation, but this can be created with 2nd and 3rd standard deviation bands as well.

Trading Logic:

The trade_spx_spreads function connects to IBKR, defines SPX options for bull call and bear put spreads, fetches market data, places orders based on the VWAP signals, and then disconnects from IBKR.

Integrating Pine Script with Python for Automated Trading

The integration of Pine Script with Python for automated trading allows for a seamless connection between TradingView’s powerful charting tools and IBKR for executing complex trading strategies like this one. For anyone interested in developing their own trading indicators, I highly reccomend TradingView, as the underlying Pine language is quite streamlined, deriving from basic JavaScript concepts. TradingView is also directly integratable with many different brokerages, making is a dynamic interactive experience.

The Pine Script below is responsible for generating the buy and sell signals in the Python trade execution script above based on specific conditions derived from the chart data.

Pine custom indicator script within TradingView:

//@version=5

indicator("Bull Call Spread Signals", shorttitle="Bull Call Signals", overlay=true, timeframe="15")

// Input Parameters

length = input.int(20, title="Standard Deviation Length")

multiplier1 = input.float(0.5, title="1st Standard Deviation Multiplier")

multiplier2 = input.float(1.0, title="2nd Standard Deviation Multiplier")

timeframe_input = input.timeframe("15", title="Timeframe")

// Calculate VWAP and standard deviation

vwap = request.security(syminfo.tickerid, timeframe_input, ta.vwap(close))

stdev = request.security(syminfo.tickerid, timeframe_input, ta.stdev(close, length))

// Calculate bands

upper_band1 = vwap + stdev * multiplier1

lower_band1 = vwap - stdev * multiplier1

upper_band2 = vwap + stdev * multiplier2

lower_band2 = vwap - stdev * multiplier2

upper_band3 = vwap + stdev * 1.5

lower_band3 = vwap - stdev * 1.5

// Plot VWAP and bands

plot(vwap, color=color.blue, linewidth=2, title="VWAP")

plot(upper_band1, color=color.green, linewidth=2, title="Upper Band 1st SD")

plot(lower_band1, color=color.red, linewidth=2, title="Lower Band 1st SD")

plot(upper_band2, color=color.green, linewidth=1, title="Upper Band 2nd SD")

plot(lower_band2, color=color.red, linewidth=1, title="Lower Band 2nd SD")

plot(upper_band3, color=color.green, linewidth=1, title="Upper Band 3rd SD")

plot(lower_band3, color=color.red, linewidth=1, title="Lower Band 3rd SD")

// Generate buy/sell signals for Bull Call Spread

buy_signal = ta.crossover(close, lower_band1) or ta.crossover(close, vwap)

sell_signal_stop = ta.crossunder(close, lower_band1)

sell_signal_profit = ta.crossunder(close, upper_band1)

// Plot signals on chart

plotshape(series=buy_signal, location=location.belowbar, color=color.green, style=shape.labelup, text="BUY CALL SPREAD")

plotshape(series=sell_signal_stop, location=location.abovebar, color=color.red, style=shape.labeldown, text="SELL CALL SPREAD (Stop)")

plotshape(series=sell_signal_profit, location=location.abovebar, color=color.red, style=shape.labeldown, text="SELL CALL SPREAD (Profit)")

// Output signals for Python script to fetch

bgcolor(buy_signal ? color.new(color.green, 90) : na, title="Buy Call Spread Background")

bgcolor(sell_signal_stop ? color.new(color.red, 90) : na, title="Sell Call Spread Background (Stop)")

bgcolor(sell_signal_profit ? color.new(color.red, 90) : na, title="Sell Call Spread Background (Profit)")

This Pine indicator calculates the VWAP (Volume Weighted Average Price) and its associated standard deviation bands. As it is currently calibrated, this script is shorter term with the timeframe initialized as the 15 minute chart. This can obviously be changed to fit the time scale of your preferred trading strategy, and is more reliable on longer-dated signal generation.

It then generates buy and sell signals when certain conditions are met, such as when the price crosses the VWAP line or specific bands. These signals are then used by the Python script, which continuously fetches the latest signals and price data from TradingView, calculates theoretical option prices using QuantLib, and executes trades based on the received signals.

The Python script fetches VWAP signals from TradingView using the tradingview_ta package and places option spread trades based on the signals. The script checks for entry and exit conditions to manage the trades, ensuring that the strategy is followed accurately.

This combination of Pine for signal generation and Python for trade execution creates a theoretical automated spread trading system where your risk is fixed to the debit transaction. It can also be set up for credit spreads of course!

The end result of the indiactor on TradingView looks something like this, where the bull call spread is bought on the crossing of VWAP and sold when there is a clear rejection on the 0.5 standard deviation band. This is, of course, just a rough concept and would need to be optimized for legitimate alpha generation.

The end result of the indiactor on TradingView looks something like this, where the bull call spread is bought on the crossing of VWAP and sold when there is a clear rejection on the 0.5 standard deviation band. This is, of course, just a rough concept and would need to be optimized for legitimate alpha generation.

This particular strategy and demonstration, even though it would have resulted in profitability in this instance, is quite dangerous without more stop triggers set in place. VWAP acts as a gravitational anchor that the price is typically pulled to; while volumetric breakouts and crossovers can sometimes extend all the way out to 3 standard deviations, it is far more common for the price to break above VWAP, fail to reach the first sell-signal band, and then fall back down to VWAP.

As long as you are lazer-focused on implementing proper risk management, with a good amount of fine-tuning, practice, and evaluation, this concept can indeed be transformed into a highly-lucrative strategy.

Distributed Systems and Blockchain

Distributed systems are critical for handling large-scale financial data processing. Technologies like Apache Kafka, Spark, and Cassandra are used to manage, process, and analyze data in real-time, providing scalability and fault tolerance.

Example: Real-time Data Processing with Apache Kafka and Spark

This example demonstrates real-time data processing using Apache Kafka and Spark. It reads data from a Kafka topic, processes it with Spark, and writes the processed data to a Cassandra database.

from pyspark.sql import SparkSession

from pyspark.sql.functions import col

# Create a Spark session

spark = SparkSession.builder \

.appName("Financial Data Processing") \

.getOrCreate()

# Read data from Kafka

df = spark.read.format("kafka").options(

kafka.bootstrap.servers="localhost:9092",

subscribe="financial_data"

).load()

# Process data

processed_df = df.selectExpr("CAST(key AS STRING)", "CAST(value AS STRING)") \

.withColumn("value", col("value").cast("double"))

# Write processed data to Cassandra

processed_df.write \

.format("org.apache.spark.sql.cassandra") \

.options(table="financial_data", keyspace="finance") \

.save()

Explanation

Spark Session:

A Spark session is created to manage the Spark application.

Reading Data from Kafka:

Data is read from a Kafka topic named “financial_data”.

Processing Data:

The data is cast to appropriate types for processing.

Blockchain for Financial Transactions

Blockchain technology ensures secure and transparent transactions in financial systems. Smart contracts can automate financial agreements, and distributed ledgers provide a tamper-proof record of transactions.

Example: Smart Contract for Automated Payments

This example demonstrates a simple smart contract for automated payments using Solidity. The contract allows a payer to send a specified amount to a payee.

pragma solidity ^0.8.0;

contract PaymentContract {

address public payer;

address public payee;

uint256 public amount;

constructor(address _payee, uint256 _amount) {

payer = msg.sender;

payee = _payee;

amount = _amount;

}

function makePayment() public payable {

require(msg.sender == payer, "Only the payer can make the payment");

require(msg.value == amount, "Incorrect payment amount");

payable(payee).transfer(amount);

}

}

Explanation

Contract Initialization:

The constructor initializes the payer, payee, and payment amount.

Payment Function:

The makePayment function allows the payer to send the specified amount to the payee, ensuring only the payer can make the payment and the correct amount is sent.

Stock Price Simulation Using Geometric Brownian Motion (GBM)

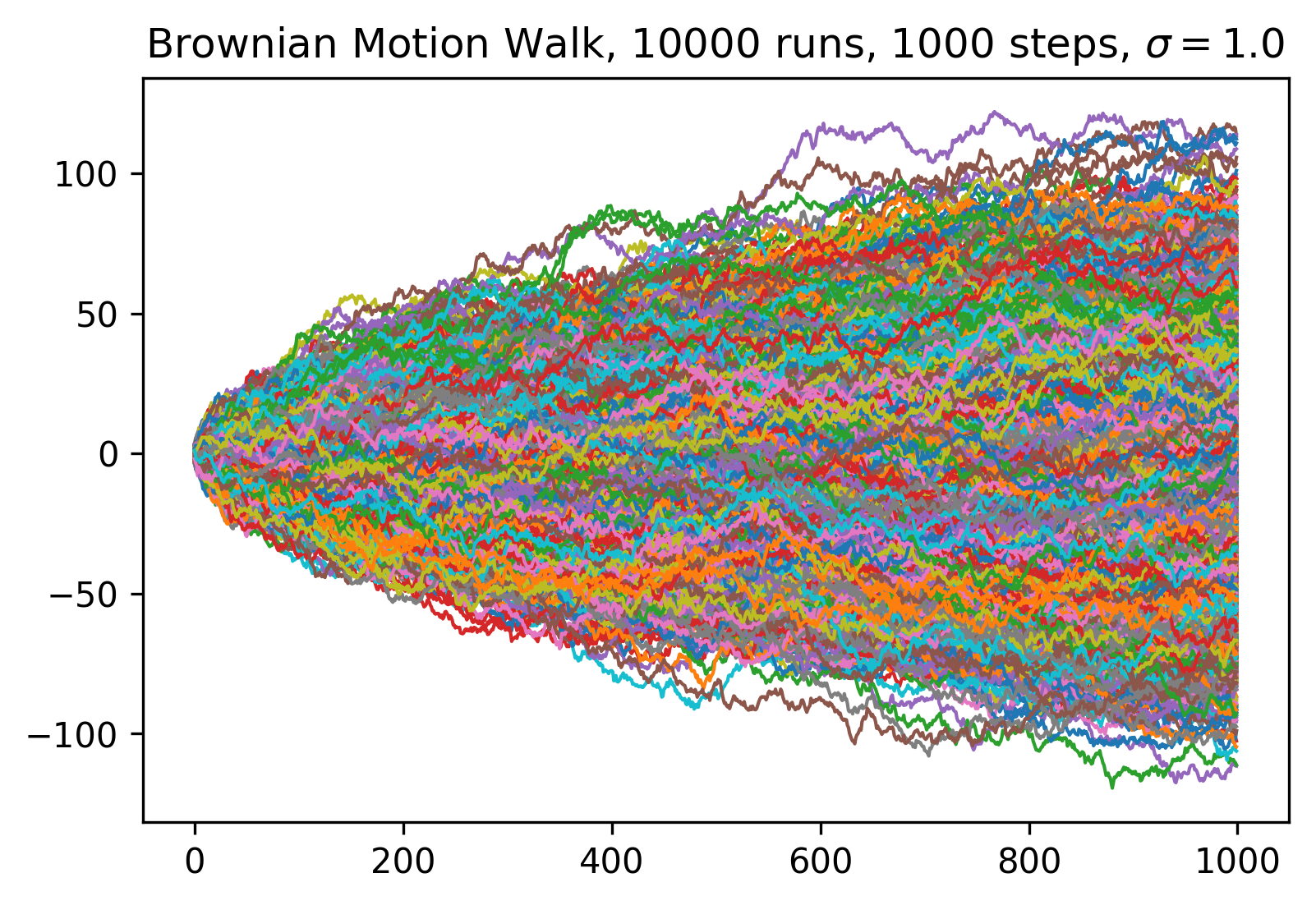

Geometric Brownian Motion (GBM) is a mathematical model widely used in finance to simulate the price paths of stocks and other financial assets. The GBM model incorporates both the deterministic trend and the stochastic component of asset prices, making it suitable for modeling the random behavior of stock prices over time.

Mathematical Formulation of GBM

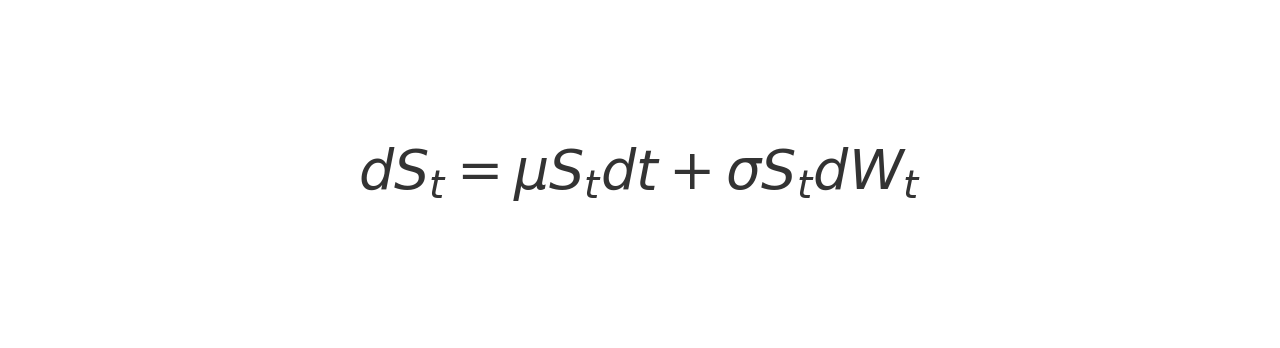

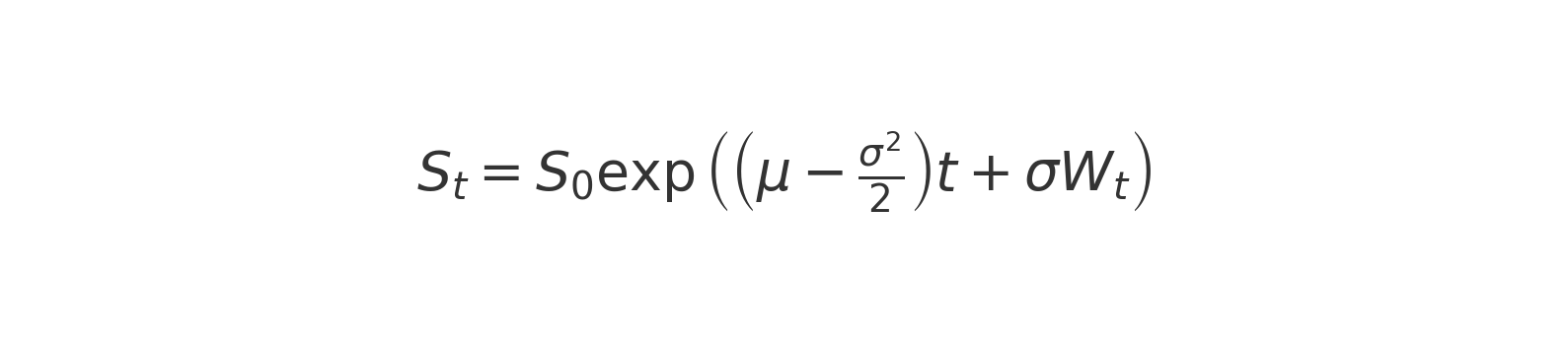

The Geometric Brownian Motion model is defined by the stochastic differential equation (SDE):

where:

- S_t is the stock price at time t .

- μ is the drift term, representing the expected return.

- σ is the volatility term, representing the standard deviation of the stock’s returns.

- dW_t is a Wiener process (or Brownian motion), representing the random component.

The solution to this SDE gives the following formula for simulating stock prices:

C++ Implementation

To frame up this simulation in C++, here are the three main components of GBM we will need to implement for simulating randomized stock price behavior:

Generating Gaussian Noise:

The function generateGaussianNoise() generates normally distributed random numbers using the Box-Muller transform, which converts uniformly distributed random numbers into Gaussian distributed random numbers.

Simulating Stock Prices:

The function simulateStockPrices() generates a vector of stock prices over a specified number of days using the GBM model. It starts with an initial stock price S_0 and iteratively applies the GBM formula to compute the stock price for each subsequent day.

Main Function:

The main() function initializes the parameters, calls the simulateStockPrices() function, and prints the simulated stock prices.

C++ Code

Simulating Stock Prices using Geometric Brownian Motion in C++:

#include <iostream>

#include <cmath>

#include <cstdlib>

#include <ctime>

#include <vector>

// Function to generate Gaussian noise using Box-Muller transform

double generateGaussianNoise() {

static double z1;

static bool generate;

generate = !generate;

if (!generate) return z1;

double u1, u2;

do {

u1 = rand() * (1.0 / RAND_MAX);

u2 = rand() * (1.0 / RAND_MAX);

} while (u1 <= std::numeric_limits<double>::min());

double z0;

z0 = sqrt(-2.0 * log(u1)) * cos(2 * M_PI * u2);

z1 = sqrt(-2.0 * log(u1)) * sin(2 * M_PI * u2);

return z0;

}

// Function to simulate stock prices using Geometric Brownian Motion

std::vector<double> simulateStockPrices(double S0, double mu, double sigma, int days) {

std::vector<double> prices;

prices.push_back(S0);

for (int i = 1; i <= days; ++i) {

double dt = 1.0 / 252; // Assuming 252 trading days in a year

double dW = sqrt(dt) * generateGaussianNoise();

double St = prices.back() * exp((mu - 0.5 * sigma * sigma) * dt + sigma * dW);

prices.push_back(St);

}

return prices;

}

int main() {

srand(time(0)); // Seed the random number generator

double S0 = 100.0; // Initial stock price

double mu = 0.1; // Expected return (drift)

double sigma = 0.2; // Volatility

int days = 252; // Number of days to simulate

std::vector<double> prices = simulateStockPrices(S0, mu, sigma, days);

for (double price : prices) {

std::cout << "Price: $" << price << std::endl;

}

return 0;

}

Explanation

Generating Gaussian Noise:

The generateGaussianNoise() function uses the Box-Muller transform to generate normally distributed random numbers. This is necessary for simulating the random component of the stock price changes.

Simulating Stock Prices:

The simulateStockPrices() function initializes the stock price vector with the initial price S_0.

For each day, it calculates the change in stock price using the GBM formula.

The stock price for the next day

S_t+1 is computed using the previous day’s price, the drift term, and the random shock generated by generateGaussianNoise().

Main Function:

The main() function sets the initial parameters and calls the simulateStockPrices() function.

It then prints each simulated stock price to the console.

Practical Applications

Risk Management:

Simulating future stock prices helps in assessing the potential risks and returns associated with different investment strategies.

Option Pricing:

GBM is used in the Black-Scholes model to price European options by simulating the underlying asset’s price paths.

Portfolio Optimization:

Simulated price paths can be used to evaluate the performance of different portfolio compositions under various market conditions.

Stress Testing:

Financial institutions use simulations to test how their portfolios would perform under extreme market conditions.

Default Probability Simulation Using Monte Carlo Methods

In the world of finance, understanding and predicting default probabilities is crucial for proper risk management and pricing derivatives. Monte Carlo simulations are a powerful tool used to estimate these probabilities by performing numerous random simulations to predict the likelihood of different outcomes. This method is particularly useful when dealing with complex financial models where analytical solutions are not feasible.

In this section, we will delve into how Monte Carlo simulations can be employed to estimate default probabilities. We will use C++ to implement a robust simulation model, assuming the default probability follows a normal distribution characterized by a given mean and standard deviation. The script will simulate a large number of random scenarios to determine the proportion of defaults, providing us with an estimated default probability.

Introduction to Monte Carlo Simulations

Monte Carlo simulations rely on repeated random sampling to obtain numerical results. The core idea is to use randomness to solve problems that might be deterministic in principle. In finance, Monte Carlo methods are used for various purposes, including portfolio risk management, black scholes options and derivatives pricing, and other portfolio optimizations. By simulating a large number of potential future paths (similar to the Brownian Motion Walk above), we can gain insights into the distribution of possible outcomes and make better informed decisions.

Implementing Default Probability Simulation

Now, let’s implement the C++ script to simulate default probabilities using Monte Carlo methods. As is standard, we’ll assume the default probability is normally distributed, with a specified mean and standard deviation. The script will generate random default probabilities, count how many times the simulated probability exceeds a threshold (indicating a default), and calculate the proportion of defaults over the total number of simulations.

#include <iostream>

#include <cmath>

#include <vector>

#include <random>

// function to generate random number from a normal distribution

double generateRandomNumber(double mean, double stddev) {

static std::default_random_engine generator;

std::normal_distribution<double> distribution(mean, stddev);

return distribution(generator);

}

// function to simulate default probability using Monte Carlo methods

double simulateDefaultProbability(double mean, double stddev, int numSimulations) {

int defaultCount = 0; // counter for defaults

for (int i = 0; i < numSimulations; ++i) {

// generate random default probability

double defaultProbability = generateRandomNumber(mean, stddev);

// check if default occurs

if (defaultProbability > 0.5) {

++defaultCount;

}

}

// return estimated default probability

return static_cast<double>(defaultCount) / numSimulations;

}

int main() {

double mean = 0.02; // mean default probability

double stddev = 0.01; // standard deviation

int numSimulations = 10000; // number of simulations

// simulate default probability

double defaultProbability = simulateDefaultProbability(mean, stddev, numSimulations);

// print the estimated default probability

std::cout << "Estimated Default Probability: " << defaultProbability << std::endl;

return 0;

}

Explanation

Generating Random Numbers

The function generateRandomNumber uses the random library to generate random numbers from a normal distribution. The std::default_random_engine and std::normal_distribution classes are employed to create random numbers with a specified mean and standard deviation. This randomness simulates the uncertain nature of default probabilities in real-world scenarios.

Simulating Default Probabilities

The function simulateDefaultProbability performs the core of the Monte Carlo simulation. It runs a loop for a specified number of simulations (numSimulations), generating a random default probability in each iteration. The generated default probability is then compared to a threshold (0.5 in this case) to determine if a default has occurred. The number of defaults is counted and used to calculate the proportion of defaults over the total number of simulations, providing an estimated default probability.

Main Function

In the main function, we define the parameters for the simulation, including the mean and standard deviation of the default probability and the number of simulations to run. The simulateDefaultProbability function is called with these parameters, and the estimated default probability is printed to the console.

Conclusion

Monte Carlo simulations offer a robust method for estimating default probabilities, especially in complex financial models where analytical solutions are challenging. By simulating numerous random scenarios, we can gain valuable insights into the likelihood of defaults and make more informed risk management decisions. This C++ implementation demonstrates how to harness the power of Monte Carlo methods for financial applications, providing a foundation for more advanced and customized simulations.

More to Come!

Stay tuned for more demonstrations and code examples showcasing various algorithms and technologies. From advanced trading strategies and AI models to distributed systems and blockchain implementations, this page will be continually updated with cutting-edge solutions and insights.

Feel free to check back regularly for new content and detailed explanations of complex financial and technological concepts!