Macro

Options, Enormous Tail Risk, and Stagflation

History is repeating itself; a data-driven review on why the 1970s and early 1980s are back in action

With an overwhelming amount of noise in the modern age and an abundance of conflicting narratives regarding the state of the global economy, it’s more important than ever to sift through the chatter and focus on the key data that drives central bank decisions. This page is my attempt to quell some of this noise; to have a conversation about the trends and patterns that appear to be repeating from several decades ago, and to go over the lessons learned (and not learned) to better understand what can be expected in the future.

History doesn’t repeat itself,

But it often rhymes

- Mark Twain, maybe

The S&P 500, Dow Jones, and NASDAQ indices all are once again at all-time-highs and the economy continues to march ahead, despite the Federal Reserve raising and holding the Federal Funds Rate faster than ever before in 2022-2023. Labor remains substantially stronger than expected with every new data print and higher unemployment is nowhere to be seen, despite recessionistas on Twitter calling for an imminent market crash with every negative economic data print since the pandemic. There is a compoundingly increasing disconnect between the stock markets and the global macro environment, as has been the case in the past before recessions, as exuberence takes the place of reason from the top down. I will admit I myself have gone short through index put option instruments in anticipation of a severe correction, notably when Silicon Valley Bank, Signature Bank, and Silvergate all blew up in March 2023 due to lousy interest rate exposure. Boy was I wrong!

As I type this, the NASDAQ index is up 56% since these bank failures occured. Everyone went short all at once when the first bank Silvergate went up, and institutions only continued to add to these massive put positions on the indices as the bank news got worse with Sillicon Valley Bank, then Signature next. It was 2008 all over again! But once the Fed cleverly implemented the Bank Term Funding Program (BTFP), it was clear liquidity was back in place and there would be no domino-effect of larger bank failures like in the GFC. All of those short positions got squeezed out, and the entire US stock market effectively became similar to the infamous Gamestop short-squeeze in January 2021. The rapid closing of these huge bearish positions on the SPX, SPY, and QQQ put heavy short-term bullish pressure on the entire market.

It’s Gamma all the way down…

It’s no secret the equity indices and the fundamental macro economy rarely (if ever) align; the two of them should almost be considered mutually exclusive of each other on any time frame but the long run. I’ve lost count of all of the times a bad data print is released in the morning and the market ends the day higher than it started. Most people see this and simply dismiss the equity markets as casinos designed to take your money, and they have every right reason to do so! Surely the markets should have dropped from this clearly bearish macro data point, but everyone decided halfway through the day to turn bullish for no reason! There is practically no transparancy involved, because that is exactly how the system is designed to work.

The truth is market maker (MM) / dealer mechanics and the predominant options chain positioning on the largest instruments utilized (index options primarily, along with the MAG 7 and ETFs like SPY, QQQ, IWM, etc.) were the reasons the market ended the day higher, despite the bearish data print. This is the same for all volatile market reactions that initially appear to make sence according to the economic data release but eventually turn around, and of course when the initial reaction is the complete opposite than the data would suggest. Those are just the best, aren’t they?

Insitutions with megalithic amounts of money at stake usually have an almost unlimited line of credit to throw at at options 0-DTES, weeklies, and futures. If there is a surprising data drop and the market drops 100 bps when a large hedgefund was still holding bullish out-of-the-money calls, you can damn well bet they are going to throw the kitchen sink at their underwater positioning to try and get it back. I’ll get to how they are typically saving their positions in a moment, but a fundamental understanding of how gamma ramps work is critical here.

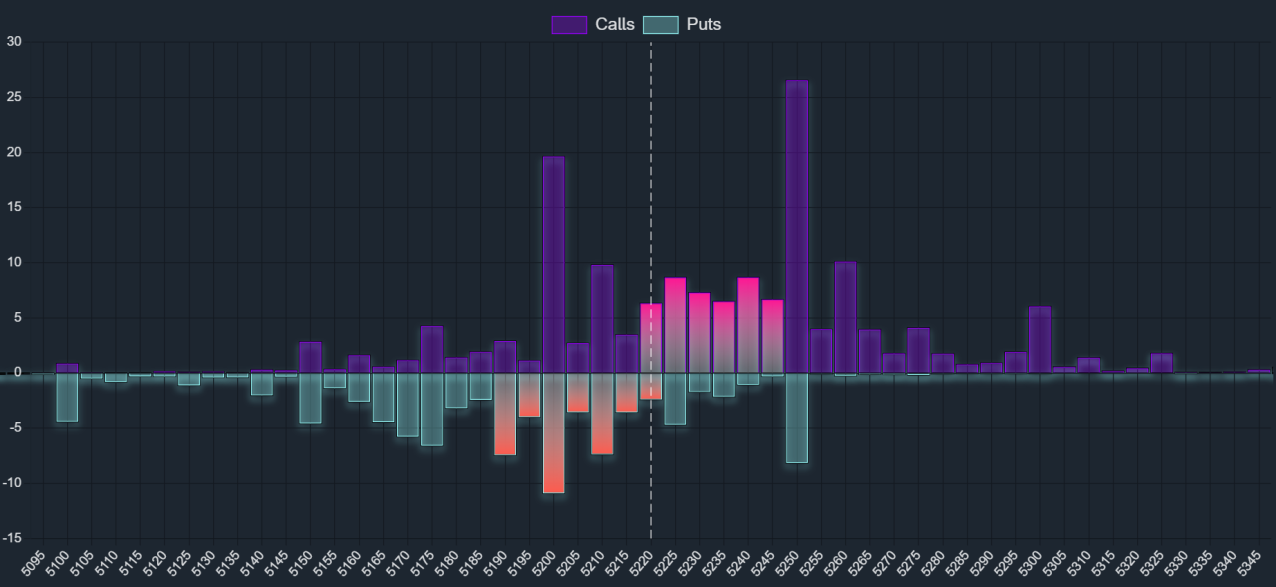

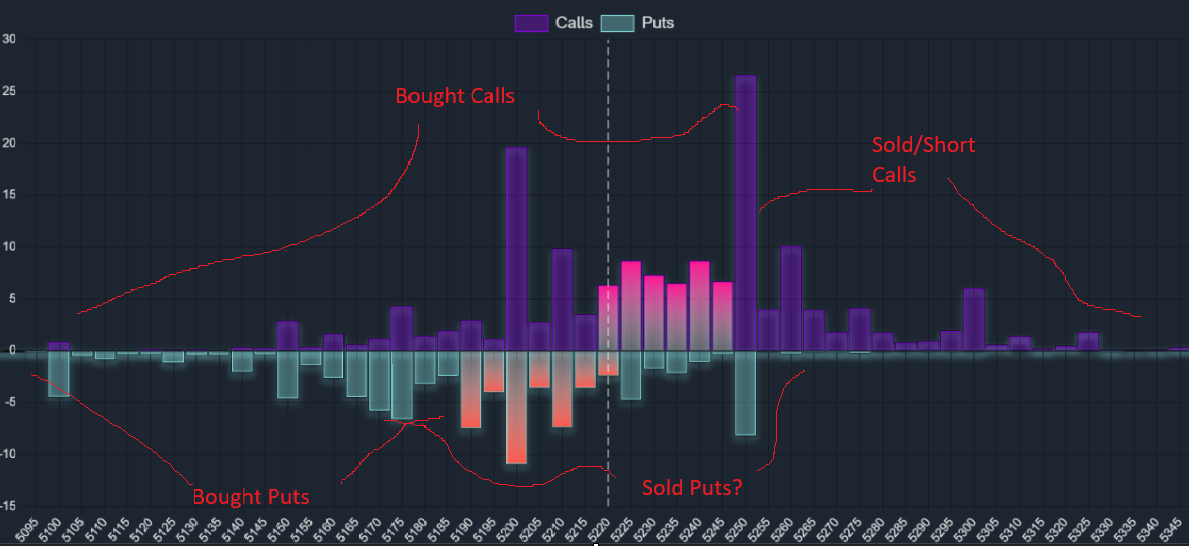

The bar chart above is a snapshot of the total gamma positioning of the SPX options chain. Gamma positioning reflects the dynamic influence of options hedging activities on the underlying asset’s price. When large short-dated options positions exist, they carry more gamma-weight and act as “gravitational centers”; this means that significant gamma at specific strike prices creates strong forces that pull the asset’s price towards these levels. Larger gamma concentrations at certain strikes (often referred to as “gamma walls”, or “call/put walls”) can stabilize the price around these points due to the hedging actions of options dealers/(MMs). They adjust their positions by buying as the price drops and selling as it rises, thereby exerting a gravitational effect on the underlying asset.

Specifically, gamma refers to the rate of change of an option’s delta with respect to changes in the price of the underlying asset.

Delta is the first derivative of the option’s price with respect to the underlying asset’s price. It measures the sensititivity of the option’s price to a $1 change in the price of the underlying asset.

So if Delta is the first derivative, Gamma is the second derivative, which measures the rate of change of delta for a $1 change in the price of the underlying.

When there is a high level of gamma, small movements in the underlying asset can lead to significant changes in delta, prompting MMs and other participants to adjust their hedges more frequently and aggressively.

At all times there is a fluctuating amount of delta and gamma open interest depending on what options retail and institutional traders are buying and selling. As there is a symbiotic relationship between calls and puts on the same underlying chain, the price will slip right through strikes that are heavily-skewed one way or the other, and will constantly find gravitational resistance at strikes that are highly contested.

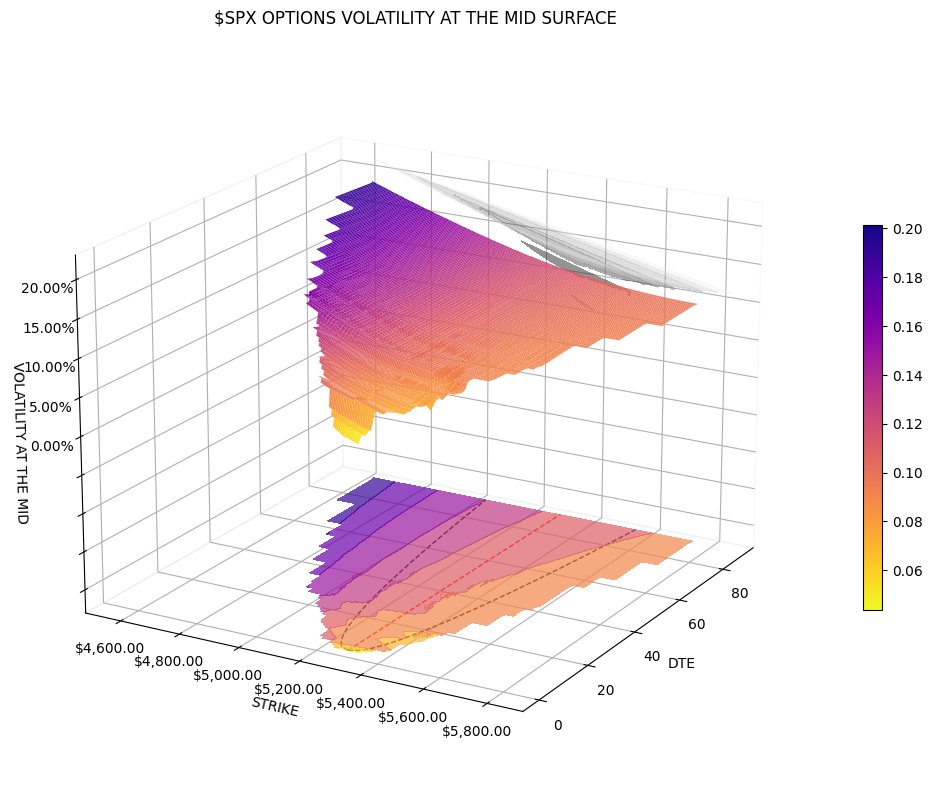

Additionally, the prices of options are influenced by the implied volatility of the underlying asset established by the market maker. If the demand for puts increases, it can drive up the implied volatility, which in turn can affect the prices of calls as well, since implied volatility is a key input in the pricing models for both types of options.

Gamma-neutral positioning involves adjusting a portfolio so its overall gamma, or sensitivity to changes in the underlying asset’s price, is zero. This is done to stabilize positions and reduce risk. This concept is similar to delta-neutral positioning, which in reality ends up being more of a theoretical point of achievement that is never totally met, as asset and contract pricing are constantly fluctuating like a living, breathing organism.

I have never once seen modern market mechanics properly summed-up in any book or internet location, as it is an incredibly deep topic that people way smarter than myself commit their entire lives to researching and understanding. But it really is as simple as this 99% of the time: The nature of the stock market indices and their movements are entirely driven by the delta, gamma, and vega environments the market finds itself in assuming all open positioning is one massive portfolio.

This is how the dealers / MMs work all day every day. They are consistently hedging against the bets retail and institutional traders are making alike to ensure consistent balance liquidity. They are also massively incentivized to constrain volatility within a reasonable fashion; this typically leads to MMs hedging market bets by going short volatility.

Gamma is typically the most important of the options greeks when it comes to the speed and resistance of price action. When the underlying asset’s price is above the gamma-neutral level, MMs are typically net short gamma. They buy the underlying asset as its price rises to hedge their position, which can fuel bullish momentum and push prices higher in a net gearing effect. Conversely, when the price is below the gamma-neutral level, MMs flip net long gamma and sell the underlying asset as its price falls, adding to bearish momentum in the same manner.

On balance, these market maker hedging dynamics creates a stabilizing effect in most market environments, with large gamma positions acting like gravity walls, pulling the underlying asset’s price back towards them depending on the size of the positioning at each strike level. If you wake up in the morning before the market session and see a huge pile of call gamma above where the current price is (aka out-of-the-money, or OTM), it is likely a good bet that there is going to be a move up in the day session. If it is a more contested situation where there a lot of calls and puts at the same strikes, often ahead of an uncertain event such as an economic data print or a Fed chair speech, then price action is more likely to be choppy. On the off-chance there are far more puts than calls, fear may be on the menu and a gamma-slide downwards is possible.

If you are a well-capitalized institution engaging in short-dated index options, you are heavily incentivized to sell volatility on the chain of your choosing in combination with going long through bullish positions. The more volatility is sold short, the lower the Implied Volatility - or IV - becomes, decreasing the cost of the call options on the chain that you want to buy.

How to save billions of dollars of underwater 0-DTEs

In 2022, the CME Group expanded its options contract offerings by introducing 0-DTE (days-to-expiry) contracts in response to growing options interest from retail and institutions alike. These products, such as SPX options, are immensely appealing to active traders looking to capitalize on intraday market fluctuations without the overnight risk associated with holding positions. Index options like SPX also get a tax beneift, so institutions are incredibly incentived to throw some money in predicting where the index will end that day.

Since these contracts have very little theta (time value premium of the option contract), they are an incredibly cheap method of hedging and speculating alike, with huge risk-reward ratios, particuarly on days that are either clearly directional or clearly rangebound. Billions of dollars are now going into the SPX 0-DTE options expiry contracts nearly every day. It is easy for automated trading algorithms to capitalize on predictive patterns of technical analysis indicators and trends, but imagine feeding options positioning data to deep learning algorithms that can 1000x the money you put at risk! And we are talking about market-moving amounts of money here. Closer-dated blocks of delta/gamma positioning can have much more influence than longer-dated positioning on the underlying, especially as institutions are incentivized to get their positioning in-the-money (ITM).

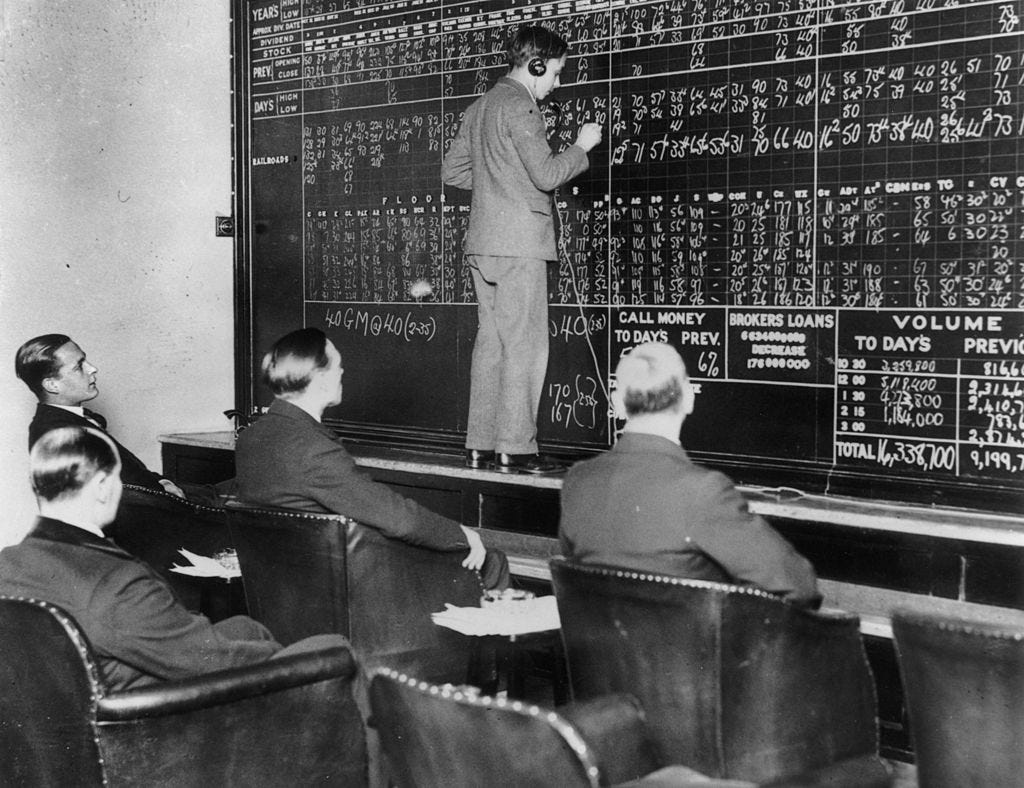

This massive amount of increasingly short-dated options interest has led to a new regime of market dynamics, where much like the olden days before market regulation was in place during the 19th and early 20th centuries, the biggest piles of money can entirely decide the outcome of the market.

The dealer is constantly hedging against any new additions to delta/gamma pushes by the big players, but there is little stopping the power of 0-DTE call buying in the face of desperation to achieve price improvement. Gone are the days where the fundamental buying and selling of the companies that make up the indices drive appropriate price improvement. The market has gone full circle, back to the earliest days where the biggest players would “corner” a particular commodity or company stock price by rapidly squeezing out the price with huge amounts of buying, or causing the price to drop in the same manner by selling their entire off their entire stakes.

If this feels crazy, well, it is in-fact crazy. The methods institutional traders now utilize to move around the markets as described above have become totally different to what Benjamin Graham, the father of long-term value investing, ever could have imagined. In fact, if he were alive today, he would likely be nothing short of horrified.

See, the massive risk-reward ratio for institutions gambling on huge piles of 0-DTEs is too good to care about what can go wrong here. It is here where we have once again found ourselves in the maniac greed-driven market conditions that can lead to black-swan events.

The trillions of 401k dollars that are being put at risk by these incredibly risky and dangerous options markets is frightening. Even though the fundamentals of how indices and underlying equities move in the short-term is radically different, the fundamental health of the global economy will always remain king in the long term, since.. you know.. it’s actually real.

Macro fundamentals, surprising data points, and earnings releases all matter just as much as the tie color that Jerome Powell is wearing at the FOMC speeches. When there are violent moves in the open markets, it is usually an effect of the price riding the gamma-slide of price acceleration that is being put in-place by the overwhelming put/call-bias at the strikes people are buying. The price stops moving hard when it has reached the end of the gamma ramp on the chain and all those ITM calls begin taking profits.

If things are really bearish for whatever reason, people continue to buy at lower OTM strikes. When there is a substantial amount of fear, everyone is piling into puts and driving up IV prices, further enhancing put values, which continues on as a gearing effect for the entire market. This is how you get flash crashes with violent recoveries, like volmagedeon in 2018 and the pandemic crash of 2020. Volmagedeon was specifically an options crash!

This is also true in the opposite direction, where it seems like market upside will never stop! After the Fed rapidly put the BTFP together, all the bearish calls sold short above the index price got gamma-squeezed out, and the gearing effect of the market maker hedging these massive amounts of calls drives prices violently upward. If people are closing out their sold calls that are getting destroyed, that is also adding bullish momentum.

Once 0-DTE SPX options were introduced, short-term market action became almost entirely controlled by the mechanics described above in regard to the shortest dated options, where there is a continuous gearing effect driven by market maker hedging depending on the net-gamma environment on the underlying indices and stocks.

So yeah, this particular aspect of the market is reminiscent of a casino where the biggest bets matter the most. Unfortunately, Big eats Small, and the world has been like this since the beginning of life itself. But, the fortunate side is that most of this is trackable with the right live data packages and work flows. Python and R are both incredible tools for shaping and displaying options chain data in visuals that can assist in rapid trading decision making.

If you have the capabilities of obtaining and understanding good dtata in this world, you have the upper hand. If you know how to leverage all of this information, you can make a lot of money.

You wouldn’t believe it, but there are active funds out there trading hundreds of millions of dollars in assets every day that are not looking at or are even aware of these market maker mechanics! Though the ones that are aware do infact push huge amounts of money into the options markets in increasing fashion. They are determined to use these mechanics alongside with their Liberian-GDP-sized-capital to their advantage wherever necessary. Here’s specifically how they do it, and why it is actually an incredibly large risk to all of us.

Let’s take another look at this SPX gamma positioning chart as an example. Anyone who has substantial margin available can sell options. If you were bullish, you can sell puts out-of-the-money (OTM) that are underneath the current price and collect the premium upfront. By selling an option rather than buying it as an opening transaction, you are collecting the option’s price directly as premium liquidity. What you are hoping for is that your option will expire OTM and you will get to keep your premium. This is risky if you don’t know what you’re doing, because if your option goes in-the-money (ITM), you are now deeply underwater. You can close the position at a loss by buying-to-close at the higher ITM price, or you can hold on to it and hope it goes back OTM and expires worthless.

Risky business, indeed.

If you are a GSIB or an extremely well-capitalized trader with market-moving money, this is fantastic news for you! If you happen to suddenly find yourself in a bad trade because of some lousy, data, relax! You can simply sell the hell out of all the options you want for free money, and then throw those funds into buying 0-DTES to push the markets back in your favor to save your underwater positioning!

Since the March 2023 bank failures, this has been the name of the game:

- Buy 0-DTE calls out-of-the-money

- Sell OTM puts to collect free money, buy more OTM calls if all is well

- If the market pulls back a bit and gamma is still positive, relax and buy the dip! Maybe sell even more puts!

- If things are getting shaky, buy some ES futures chunks to further push the markets in your favor

- If none of this is working, sell more puts. The closer to the money, the larger the premiums!

- Rinse and repeat!

This isn’t just selling volatility. It’s betting the house, the wife, and the kids all on one outcome.

So this is totally awesome, and markets are going to go up forever because institutions can just sell all the puts they want, buy 0-DTE calls, and keep this circus going into perpetuity! Right?

Not exactly, though it does sometimes feel this way these days.

The tail risk here should be obvious, and goes in both directions. We already experienced the effects of these dynamics to the upsdide after the BTFP was enacted in March of 2023 to provide liquidity to banks for a year. If insitutional traders sell too many calls because they think the market has topped out, and some unforeseen news or event suddenly moves the markets even higher into their sold positioning, this creates a gamma-squeeze to the upside.

Similarly, if they sell too many puts and get caught with their sold positioning too far underwater to save it, the result is a knife downwards. The degree of how far down the gamma-squeeze goes in these situations depends on net options positioning on the indices as well as the dealer delta/gamma environment. If they get caught selling too many puts in both a delta-negative and gamma-negative environment, the consequences can be totally catastrophic for the equities markets. We have gotten very close to another options market meltdown from this exact kind of situation already a handful of times since the banks failed last year.

Creative methods involving selling volatility are commonplace and diversified now, and we are pretty much in deriviate uncharted territoty. Lately, in peak desperation, there have even been instances where in-the-money puts are sold in efforts to drive upward price action! A single bearish headline can trigger a 100-300 basis point drop as sold gamma on the options chain squeezes downward, leaving these traders who sold vol short massively underwater. Anybody who is underwater sold puts to this degree only one option to attempt to save their positioning, and it is the cycle I described earlier of selling more puts and buying more calls. They have to dig themselves deeper and deeper to get themselves out.

But this simply does not work under gamma-neutral and delta-neutral, where the market maker is actively fighting against these traders. The more puts sold, the more market makers must hedge, intensifying the consequences of selling volatility too hard. Greater uncertainty and fear during market slides can lead to perpetual put buying, causing catastrophic consequences for put sellers. If no immediate source of liquidity can be found, they will be at risk of being margin called and liquidated. And by ‘they’, I mean practically every institutional participant engaging in these trades, and it goes all the way up to the biggest GBIBs.

Don’t get me wrong, most of these traders engaging in these incredibly risky short-vol strategies have access to all kinds of liquidity, and they can scrape together instrumental derivaties beyond human comprehension to obtain the funds necessary to save themselves from liquidation. There is one source in partciular that seems to be the overwhelming majority of liquiduty participants have been abusing to keep this circus going, but the clock is ticking.

Remember “Inflation is Transitory”?

Let’s pivot for a moment and come back to the equity and options markets later.

Below is the year-over-year change in all of the core components of the CPI index for the United States. You see that dotted blue line? That’s the Fed’s target for year-over-year growth at 2%. As you can see, we’re not only below it, the indices are showing signs of finding resistance in this upper range.

I have separated the Energy index out on the right Y-axis as it is traditionally the most volatile index with much higher year-over-year changes. Energy and producer-price indices did fall into deflationary negative yearly growth for a little bit there, but recent pressures on oil pricing have pushed these back into positive territory again as of March 2024.

So why am I talking about inflation right now? Surely we’ve all had enough of this since the pandemic!

Unfortunately, anyone who lived through the 1970s and 1980s should understand how annoying and ‘sticky’ inflationary periods can last in modern economies. While most people know it happened, few understand what ended this period. I am going to break down why we are not likely to see a quick end to inflation, and why this is going to be catastrohphic for the current strategies in place to keep the equity markets propped up. The Fed chair Powell himself recently said that his confidence that inflation will slow “is not as high as it was.”

The last inflationary crisis: a brief history

The 1970s and early 1980s were marked by significant economic turmoil, characterized by high inflation, slow economic growth, and high unemployment. This period gave way an economic status that is not well-understood; stagflation.

In the first half of this cycle, as consumer- and producer-side prices began to increase exponentially, the Federal Funds Rate (FFR) acheived a peak of 12.92 in July 1974. Most of this first spike was directly caused by heightened geo-political turmoil in the middle east; OAPEC imposed an oil embargo against the United States and other countries supporting Israel during the Yom Kippur War. This led to a dramatic increase in oil prices, quadrupling from about $3 to nearly $12 per barrel, causing widespread global economic disruptions and energy shortages.

The record-high rates at the time were enough to cause a slowdown in consumer lending and purchasing activity, which naturally led to a soft recession that was officialy declared afterwards to have started in November 1973 and lasted until March 1975.

During this period, the US economy faced large rises in producer prices that were caused from producer-side inflation rather than the demand-driven consumer-side inflation. We saw a deathly combination of stagnant economic growth with high unemployment and rising prices. Inflation was exacerbated by the loose monetary policies of the late 1960s, which had been implemented to finance the Vietnam War and domestic social programs without raising taxes. Additionally, the collapse of the Bretton Woods system in the early 1970s led to the devaluation of the US dollar, which is an entire diffirent conversation.

Investment spending plummeted, affecting everything from residential construction to business inventories. High inflation rates eroded purchasing power, making everyday goods more expensive. Unemployment rose, and economic uncertainty became pervasive. The Federal Reserve’s initial response was to tighten monetary policy, but it was not sufficient enough to slow down the economy. Sound familiar?

Consumer- and producer-side inflation failed to get back to the 2% goal, and eventually the asset bubble was entirely re-ignited in the later 70s with a second larger spike in inflation.

The Middle East problem got much worse with the Iranian Revolution in 1979, which directly led to the oil crisis, where oil supplies and trading routes were suddenly disrupted, leading to to a dramatic increase in oil prices. The previous oil embargo by OPEC in 1973-1974 also set the stage for these inflationary pressures in advance.

Meanwhile the Fed and US government was fairly lazy with their spending and easy money policies aimed at reducing unemployment, which ultimately led to higher inflation.

When you get high inflation and high unemployment, simultaneously with little-to-no GDP growth, this is Stagflation. The Fed’s response to the intial inflation spike was inadequate (remember “inflation is transitory”? I do.); policymakers were reluctant to raise interest rates high enough to combat inflation effectively due to fears of exacerbating unemployment and slowing economic growth.

The US was in a critical position once the 70s rolled into the 80s, and the global economy needed someone to save the US at any means necessary.

Enter Paul Volcker, the new Fed Chair appointed by Carter in 1979.

When Volcker entered the stage, he implemented a series of aggressive interest rate hikes to combat inflation, first to 17.6%, then down to 9% for a short break, then right back up to the all-time-high of 19%. (So seriously guys, stop complaining about 5.5%). This did eventually bring inflation back under control, but led to a severe recession practically immediately, with spikes in unemployment and a slowdown in GDP growth.

So where are we on this chart in respect to today?

The answer is probably 1976 to 1979.

While the past will obviously not repeat itself, many of the variables that set the second larger wave of inflation in place, which respectively led to the deeper recesion of the early 1980s, are being set in motion once again.

Supply Shock

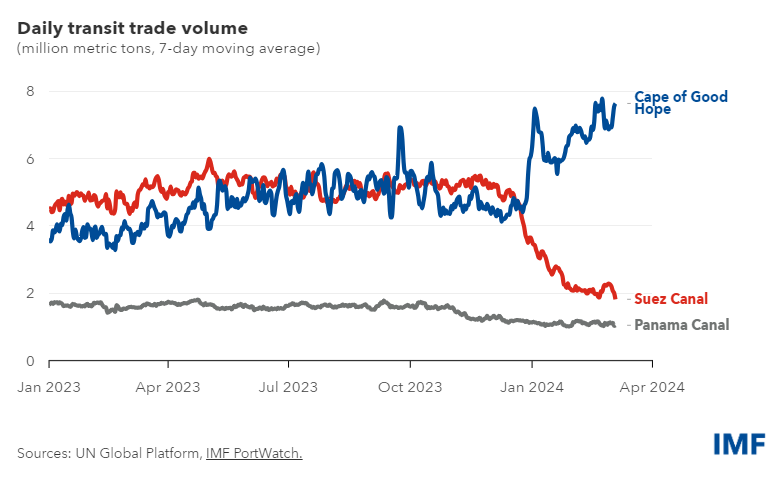

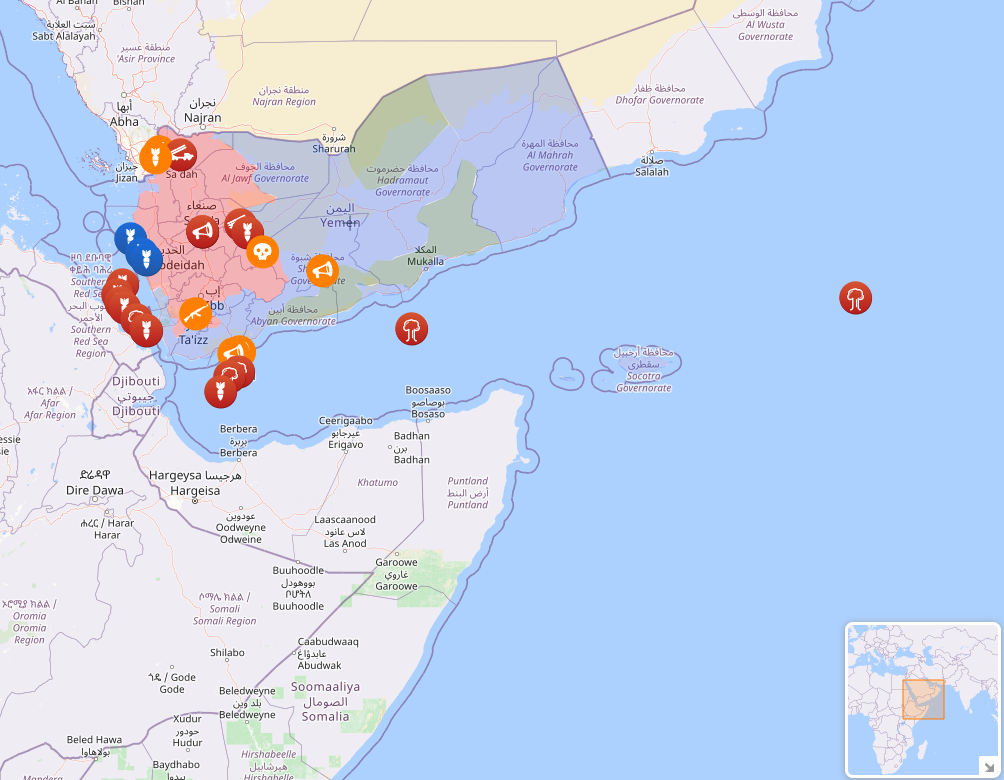

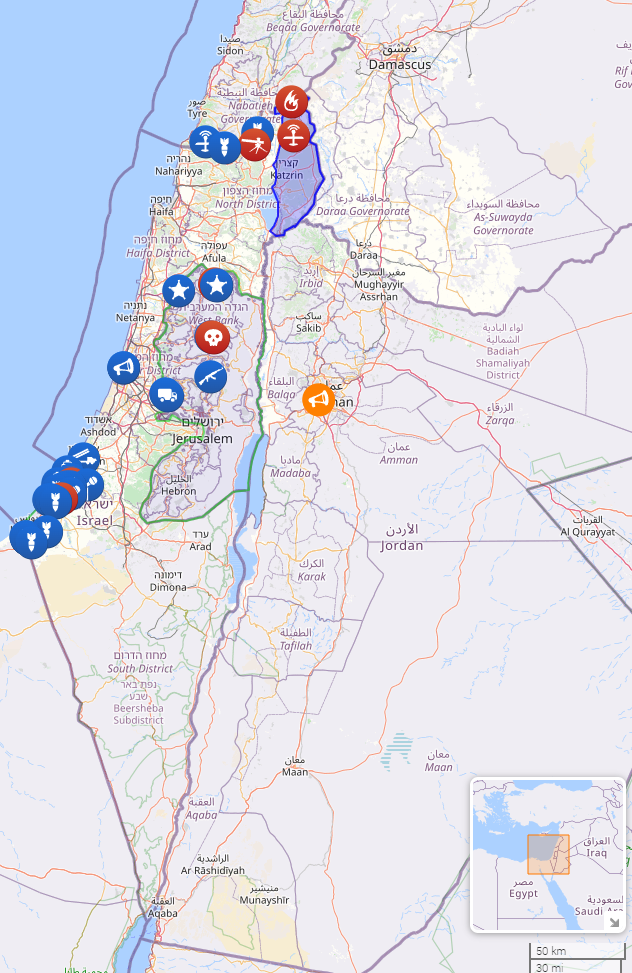

Recently, we’ve seen heightened geopolitical tensions that are significantly impacting economic conditions. The conflict involving the Houthis in the Red Sea has led to disruptions in global shipping routes, forcing major companies to reroute and consequently increasing costs and shipping times. This is reminiscent of similar Middle East escalations in the 1970s that ended up driving the gas crisis, setting off the stagflationary period back then. This has exacerbated inflationary pressures, particularly in the energy sector. Concurrently, the ongoing Israeli-Hamas conflict is contributing to instability in the Middle East, further complicating the economic outlook.

The IMF chart above takes data directly available on their portwatch dashboard, which I reccomend checking out here: IMF Portwatch

Houthis indiscriminantly firing on cargo ships has drastically reduced the traffic volume through what has traditionaly been the most important global trade choke-point in the world. The issue is also ongoing and difficult to contain. The Houthis are being directly supplied by Iran, and have shot down numerous US drones.

This isn’t inherently a problem that is going to go away quickly outside of significant changes in Middle Eastern power dynamics, which itself is a messy trifecta of differing ideologies between Saudi Arabia, Israel, and Iran.

If you think about how much money it costs to strap some C4 explosives to what is effectively an Amazon delivery drone, and send it off as a suicide bomb, we’re maybe talking about a few thousand dollars per iteration. And the Iranian military has plenty of technological capabilities and resources to continue to disrupt the shipping environment for quite a long time, especially if Israel continues its campaign in Gaza, the West Bank, and now Lebanon, which are directly against Hamas and other quasi-Iranian proxy-groups.

Snapshots taken 5/21/2024. Source: liveuamap.com

Snapshots taken 5/21/2024. Source: liveuamap.com

The journey from Shanghai to Rotterdam through the Suez Canal is significantly shorter than going around the Cape of Good Hope. The route through the Suez Canal is approximately 12,000 miles, while the route around the Cape of Good Hope extends the journey to approximately 14,700 miles. This difference means that the Cape of Good Hope route is roughly 23% longer than the Suez Canal route for this specific route, and translates to roughly 30-50% longer for most Asia-Pacific ports to Europe or the Americas (don’t even think about the Pacific ocean; it’s half the planet’s surface).

Don’t even get me started on the long-term repercussions of Russia potentially annexing Ukraine’s wheat-rich provinces along the Black Sea. No matter how the conflict resolves, Russia’s intentions to control these crucial regions—home to many grain farms that are vital for the food supply of African and Middle Eastern countries—are clear. This situation could significantly disrupt global food security and price stability, especially in the event Russia ends up victorious in Ukraine and re-diverts these wheat routes throughout themselves and other BRICs countries.

To say this is a global economic problem is an understatement.

Shelter Crisis

Outside of all of the geo-political risk to energy inflation, there is an ongoing housing shortage left over from the last financial crisis that is likely to keep housing prices fairly insulated against proper deflation any time soon; even amid potential economic downturns, housing prices remain relatively high, as the supply cannot meet the gigantic demand. The gap between available housing and the growing population needing homes prevents prices from dropping to more affordable levels, thereby insulating the market from deflationary pressures.

Despite the overly-optimistic outlook of the equity markets, the average American consumer is facing significant financial strain. Delinquencies are rising, credit card reliance has never been higher, and savings are approaching rock bottom. Early warning signs of consumer distress have been evident, but the severity of the situation is escalating. The Personal Saving Rate hit its lowest point well before the 2008 financial crisis, highlighting the precarious position of many consumers even before recent economic challenges. Savings going down combined with rising living costs screams people are less prepared to handle any financial shocks.

The early warning signs of a consumer recession were there before, and they are now here once again. All of the excess savings that were fueled by the ZIRP-era and stimulus checks are now gone.

Consumers are experiencing sustained high prices for food and groceries, with no signs of relief. This continued inflation in essential goods further strains household budgets, exacerbating the financial pressure on consumers already dealing with high housing costs and stagnant wages.

So, to absolutely no one’s surprise, the Federal Reserve’s incredibly limited tool of raising interest rates to combat producer-side inflation is having absolutely no effect on the high prices the consumer is facing. While higher interest rates aim to cool the overheating economy by curbing spending and investment and thus reducing inflation, they have not succeeded in lowering the costs of essential goods and services for consumers, as this is something that is simply out of their direct control.

Large corporations experience the costs of higher rates and inflation in waves, unlike the consumer. The high prices that corporations are anchoring are caused by a multitude of reasons, but primarily it is them preparing for what is ahead; the massive amount of corporate debt maturing at higher rates.

Take a look at how much construction spending alone has come from the post-pandemic free-money era before Powell started raising rates in March of 22!

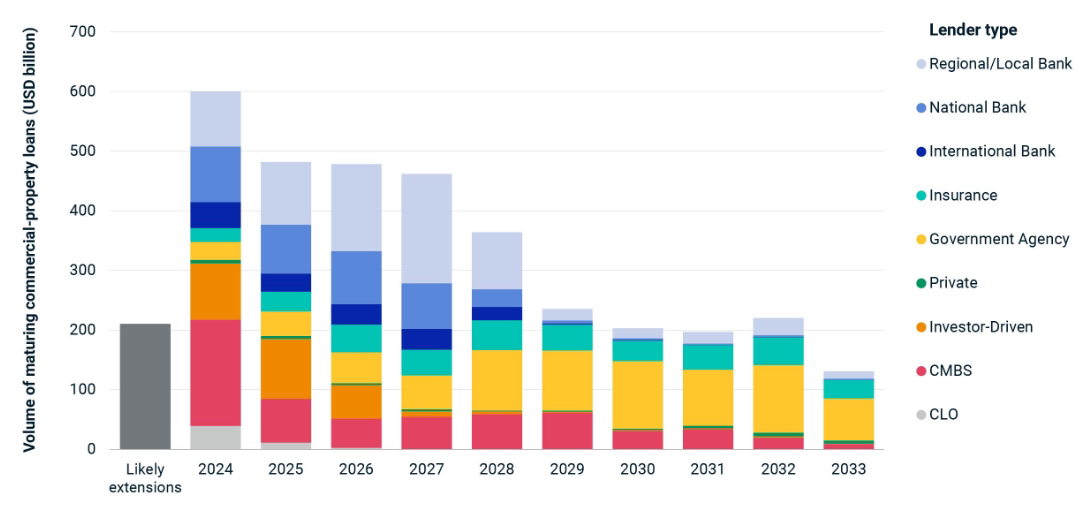

The maniac spending that came from the ZIRP era post-covid has halted in its tracks, especially as the office commercial real estate problem becomes more pronounced. Most of the spending that has happened since 2020 was through almost 0% short-dated mezzanine/bridge debt. Now most of that is coming due to mature, and there are a whole lot of people and companies that need to decide whether to refinance at 5.5% interest rates (again, when they came into their project close to 0%!) or sell off their asset entirely.

The bulk of this maturing commercial real estate debt is held by US regional banks. This concentration poses a significant risk to these financial institutions, as they may face substantial losses if properties cannot be refinanced or sold at favorable prices.

We have not yet seen a significant slowdown in building permits and new housing coming online, though is going to be a significant drop off of new construction of all kinds after 2025, as new projects have largely slowed down due to the higher rates. This is one of many examples of how economic responses to certain events can take years to fully play out. Rates remain high, and mortgage rates remain even higher.

Basicaly, the entire corporate world is bracing for impact. Due to the complexity of all of these economic-geo-political events, the fallout from all of this mass exuberance has felt a bit like this:

So whether or not housing and CRE prices plummit is going to largely depend on the health of the widespread credit environment. Turbulance can be expected as mass refinancing takes place on the commercial side. If there are a multitude of distressed operators who are also involved in securitized CMBS and RMBS products, there is a significant probability that securitized assets of all kinds begin to be sold off en-masse to meet capital requirements of refinancing maturing debt. This is a problem, again, that drives all the way up to the biggest GSIBs. Anyone who is heavily reliant on the securitized markets are going to have a really bad time if the events of 2006-2008 repeat, where there was a sudden and unexpected selloff of MBS and CLO assets to meet margin calls.

Japan: The Yen Carry Trade and the black hole of liquidity

Okay, okay.

So options, inflation, rates, supply shock, debt maturities…now Japan?!

Yes, now Japan, dear reader.

The inflation story above is largely true for most of the G7 economies. The main outliar that is going to end up being the key to all of this is, you guessed it, Japan!

Japan’s central role in the global financial system, particularly through a concept that is known as the yen carry trade, cannot be overstated. This is the core of it all, the very fabric of the financial universe we have accidentally found ourselves in. This mechanism is simple, allow me to describe:

Picture yourself as a US bank in 2020-2021, and you need to put your depositor funds somewhere risk-free, so you would typically put them into safe assets like US Treasuries. Suddenly, the Fed raises rates in 2022 and all of those US Treasuries you have been holding are now underwater.

What you do with these treasuries as a US Bank - say they were bought at 2-3% and the US FFR is now at 5.5% - is you take them to Japan, where their rates are between -0.1% and 1%. They’ve been in a period of stagflation for decades, and are desparate for their own investors to take out money and invest into the Japanese economy, so this ultra-low interest rate environment is a unique component of Japan’s economic policy.

So you’re the US bank and you elect to deposit these underwater US Treasuries into the Japanese banks. The Japanese banks love these US Treasuries because they are still higher than their local interest rates; this is the reason Japan (and China for sort of similar reasons) are the single largest foreign holders of US Treasuries in the world.

Since you’re investing into this mutual agreement that is good for both yourself and the Japanese bank, the Japanese banks are often willing to provide you leveraged margin funds in return for doing business to be able to do whatever the US banks want with, sometimes in excess of 20-30x the initial deposit! So you are getting an injection of new capital in return for the carry trade through these margined funds, which you can now lend out in mass through credit card loans, auto loans, really anything to anyone you can possibly lend to! After all, you need to make money against the interest differential on the yen carry trade, otherwise the benefit of going to all this trouble becomes worthless.

So therein lies the big question, Mr/Mrs US Bank. Where are you going to put those margined funds?

Things are beginning to look a little grim here and there. The US election is approaching, and the impacts will certainly have global ramifications of all sorts, so longer-term uncertainy is about as high as it can be. The Russia-Ukraine war is well into its second year with no signs of stopping anytime soon, and Middle Eastern dynamics are only showing signs of continued escalation, potentially leaking over into a prolonged shipping and oil crisis. You don’t want to invest in US treasuries, because the Fed won’t fully promise to cut rates this year, and the inflation data keeps coming in hotter than expected or flat, not down. The US labor economy is still strong, but the equity indices are entirely disconnected from 90% of the actual companies in the indices, who are consistently lowering guidance for future earnings due to a slowdown in consumer spending.

The only thing you can really do is pump equities through the MAG7 giants like Microsoft and Nvidia, who are making momumental-sized promises. Do you care if these massively overstated AI claims end up becoming material or not? Do you care if generative AI is actually the future? Of course not!. You only care that the current narrative supports these companies as instruments of deploying your margin liquidity.

And of course, the riskiest asset of them all, the 0-DTE index option, becomes an immediate favorite as it was convinently introduced in 2022.

So yeah, full circle now.

Global Contagion

Japan is now beginning to see the inflation it has long sought, marking a potential end to its deflationary era that began with the asset bubble collapse in the early 1990s. With inflation rising, the BOJ has already ended its 16-year yield-curve control policy and may soon shift to a fully positive interest rate environment. Even a modest rate hike, from 0.5% to 1%, represents a 100% increase, which would have significant implications for leveraged positions held by US banks.

If the BOJ raises rates even a little bit, US banks will face higher margin requirements on their yen carry trades that are largely fueling the liquidity of the US credit market. Banks have relied on the differential between US and Japanese interest rates especially since ZIRP ended to make their trades profitable. As Japanese rates rise, the cost of borrowing in yen increases, reducing the profitability of these trades.

The yen is at critically weak levels above USDJPY 150. The Ministry of Finance has hundreds of billions in reserves to stave off a total yen collapse for now, but eventually those reserves are going to run out, especially if their interventions continue to prove entirely inefective as they have for the last couple of months.

Those huge red candles are open-market interventions by the Japanese Ministry of Finance, who has been very transparent on their intention to keep USDJPY no higher than 160.

They may not have long at all until they are forced to rasie their own rates. This would be a big problem for US bond markets, as the attractiveness of JGBs will suddenly become much higher, and the foreign sell-off of US Treasuries could be nothing short of devestating. I’m sure I don’t have to spell out the seriousness of a US Treasury liquidity crisis. Let’s just hope it doesn’t come to this.

Regardless of what happens with US Treasuries and the FFR here, the raising of Japanese rates to combat their own inflation (which is highly dependant on oil and imports) is something Japan can not afford to ignore anymore, despite the potential negative diplomatic implications. Yellen herself has spoken out against the issue, of course because she knows all of this as well.

If there is a BOJ interest rate hike, this could rapidly lead to forced asset sales to cover these margins, reminiscent of the 2006 pre-GFC scenario. During that period, the narrowing spread between US and Japanese rates led to the liquidation of MBS and related assets by hedge funds, exacerbating the financial crisis. Today, the stakes are even higher, as major US banks are deeply engaged in this trade, using depositor funds for leverage.

The implications of a significant shift in Japan’s monetary policy are the centerpeice of this entire rhetoric I have laid out today. The potential for margin calls and forced asset sales from a BOJ hike could destabilize markets that are already under pressure from geopolitical and economic uncertainties. The yen carry trade has been a crucial source of cheap funding for US banks and other global financial institutions to keep credit markets alive when local interest rates are high. A disruption in this trade could lead to a credit market liquidity crunch, and potentially a steep crash in US Treasurys, forcing institutions to sell off assets at depressed prices, further exacerbating potential market volatility ahead.

Conclusion

Is all of this certain to happen this way? Of course not! The GSIBs and central banks alike are all obviously capabale of coordinating as much as possible to ensure there is not a global economic meltdown. And to some extent I hope they do and are legitimately successful in solving this problem, but I simply can not currently fathom how they will.

The financial interplay between Japan and American banks serves as a large vulnerability in our global financial system. If there is a breakdown in the carry trade, the leverege to keep the US equity markets up is going to go poof, along with any assets sold off due to mass margin calls and asset sales.

I haven’t even touched on the US Regional bank risk to our own US Treasury yields increasing beyond 5% on the 10 year. Perhaps I will add that later on. But for now, I am tired, and generally disheartened by the decisions our economic policy leaders have chosen to take.

I choose to carry on faithful that people much smarter than myself are working hard on this issue and are going to figure out how to avoid the consequences of ignoring tail risk, and in the meantime perhaps I can find a good job and place to settle down with my new fiance and three cats.

It has taken me a long while to accept, but I do believe there is a strong possibility that the remainder of the 2020s decade will be characterized by stagflation. I remain skeptical about any imminent reduction in US interest rates, as the credit markets would blow up. Despite the Fed’s aggressive rate hikes, inflation is likely to stay above their 2% year-over-year growth target as geo-political risks remain at large, putting inflationary pressure on broad commodities and energy. Despite any EV company’s efforts to convince you, we still live in a society where oil is the main driver at the beginning of the value-chain for nearly every consumer product. We are entering a period that is taking elements from both the 1970s-1980s and the 2008 GFC, where Japan’s economy has been pillaged (with consent) by outside banks who are desparate to keep equities up and loans flying off the shelves.

I really have no earthly idea how this is going to end. But I have my popcorn, and I hope you do to.

If you have any questions or want to chat about any of the topics on this page, hit me up on the Contact page.

Thank you for reading this article,

Benjamin Pachter

Future topics:

Basel 3

Regional Banks and US Interest Rate Risk:

Check out this paper by the OFR on US bank risk to rises in US Treasury yields: link